DELTA2 guidance on choosing the target difference and undertaking and reporting the sample size calculation for a RCT_Review

DELTA2 guidance on choosing the target difference and undertaking and reporting the sample size calculation for a RCT_Review

Information

link: https://www.bmj.com/content/363/bmj.k3750

Introduction

- RCT(randomised controlled trials)

- Properly conducted, randomised controlled trials are considered to be the best method for

- assessing the comparative clinical efficacy and

- effectiveness of healthcare interventions,

- providing a key source of data for estimating cost effectiveness

- Properly conducted, randomised controlled trials are considered to be the best method for

- priori sample size calculation

- Central to the design of a randomised controlled trial

- ensures that the study has a high probability of achieving its prespecified objective

- The difference between groups

- used to calculate a sample size for the trial (known as the target difference) is

- the magnitude of difference in the outcome of interest that

- the randomised controlled trial is designed to reliably detect

- The DELTA2 project,

- commissioned by the United Kingdom’s Medical Research Council/National Institute for Health Research Methodology Research Programme and

- aimed to produce updated guidance

- for researchers and funders

- on specifying and reporting the target difference (the effect size)

- in the sample size calculation of a randomised controlled trial.

- we summarise

- the process of developing the new guidance, as well as

- the relevant considerations, key messages, and

- recommendations for researchers determining and reporting

- sample size calculations for randomised controlled trials

Box 1: DELTA2 recommendations for researchers undertaking a sample size calculation and choosing the target difference

- Begin by searching for relevant literature to inform the specification of the target difference.

- Relevant literature can:

- relate to a candidate primary outcome or the comparison of interest, and;

- inform what is an important or realistic difference

- for that outcome, comparison, and population.

- Relevant literature can:

- Candidate primary outcomes should be considered in turn, and

- the corresponding sample size explored.

- Where multiple candidate outcomes are considered,

- the choice of the primary outcome and target difference should be based on

- consideration of the views of relevant stakeholder groups (eg, patients), as well as

- the practicality of undertaking such a study with the required sample size.

- The choice should not be based solely on

- which outcome yields the minimum sample size.

- Ideally, the final sample size will be sufficient for all key outcomes,

- although this is not always practical.

- the choice of the primary outcome and target difference should be based on

- The importance of observing a particular magnitude of a difference in an outcome,

- with the exception of mortality and other serious adverse events,

- cannot be presumed to be self evident.

- Therefore, the target difference for all other outcomes needs

- additional justification to infer importance to a stakeholder group.

- The target difference for a definitive trial (eg, phase III) should be one

- considered to be important to at least one key stakeholder group.

- The target difference does not necessarily have to be the minimum value

- that would be considered important

- if a larger difference is considered a realistic possibility or would be necessary to alter practice.

- Where additional research is needed to inform what would be an important difference,

- the anchor and opinion seeking methods are to be favoured.

- The distribution method should not be used.

- Reference for the anchor and the distribution method

- Specifying the target difference based solely on a

- standardised effect size approach should be considered a last resort,

- Where additional research is needed to inform what would be a realistic difference,

- the opinion seeking and the review of the evidence base methods are recommended.

- Pilot trials are typically too small to inform what would be a realistic difference and

- primarily address other aspects of trial design and conduct.

- Use existing studies to inform the value of key nuisance parameters

- that are part of the sample size calculation.

- For example, a pilot trial can be used

- to inform the choice of the standard deviation value for a continuous outcome and

- the control group proportion for a binary outcome,

- along with other relevant inputs such as the amount of missing outcome data.

- Sensitivity analyses, used in the sample size calculation, should be carried out.

- which consider the effect of uncertainty around key inputs

- (eg, the target difference and the control group proportion for a binary outcome)

- which consider the effect of uncertainty around key inputs

- Specification of the sample size calculation, including the target difference,

- should be reported according to the guidance for reporting items (see table 1)

- when preparing key trial documents (grant applications, protocols, and result manuscripts).

- should be reported according to the guidance for reporting items (see table 1)

Development of the DELTA 2 guidance

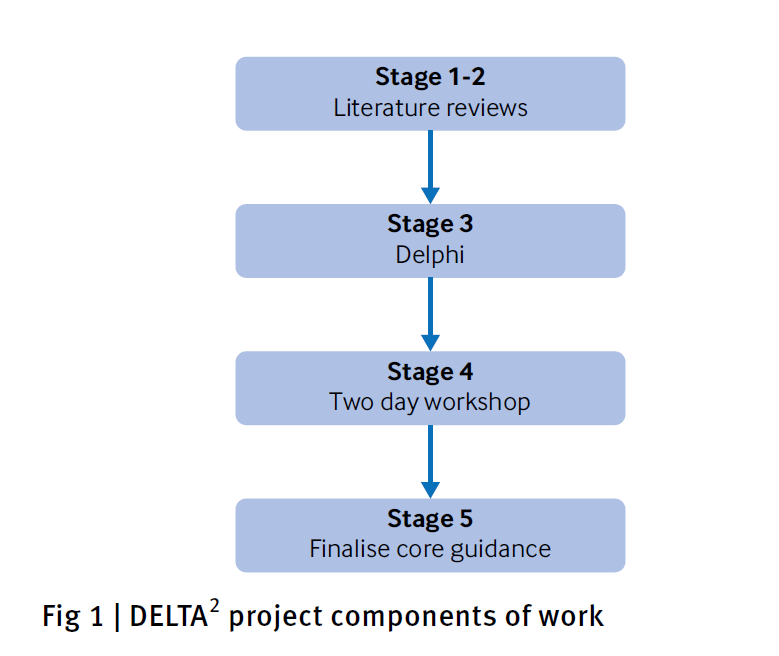

- The DELTA2 guidance is the culmination of a five stage process

- The core guidance was provisionally

- finalised in October 2017 and

- reviewed by the funders’ representatives for comment

- (Methodology Research Programme advisory group).

- The guidance was further revised and finalised in February 2018.

- The full guidance document incorporating case studies and relevant appendices is available here.

- Further details on the findings of the Delphi study and the wider engagement with stakeholders are reported elsewhere.

- The guidance and key messages are summarised in the remainder of this paper.

The target difference and sample size calculations in randomised controlled trials

- The role of the sample size calculation is

- to determine how many patients are required

- for the planned analysis of the primary outcome to be informative

- It is typically achieved by

- specifying a target difference for the key (primary) outcome

- that can be reliably detected and the required sample size calculated

- The precise research question that the trial is primarily set up to answer

- will determine what needs to be estimated in the planned primary analysis,

- which is known formally as the “estimand”

- The target difference should be a difference that is appropriate for that estimand.

- The target difference should be viewed as important by

- at least one (and preferably more) key stakeholder groups—

- that is, patients, health professionals, regulatory agencies, and healthcare funders.

- In practice, the target difference is not always formally considered and

- in many cases appears, at least from trial reports, to be determined on convenience, the research budget, or some other informal basis.

- at least one (and preferably more) key stakeholder groups—

- The target difference can be expressed as an

- absolute difference

- (eg, mean difference or difference in proportions) or

- relative difference

- (eg, hazard or risk ratio)

- is also often referred to, rather imprecisely, as the trial “effect size

- absolute difference

- Statistical calculation of the sample size is far from an exact science

- Firstly, investigators typically make assumptions

- that are a simplification of the anticipated analysis.

- For example, the impact of adjusting for baseline factors is difficult to quantify upfront,

- and even though the analysis is intended to be an adjusted one

- (such as when randomisation has been stratified or minimised),

- the sample size calculation is often conducted on the basis of an unadjusted analysis.

- and even though the analysis is intended to be an adjusted one

- Secondly, the calculated sample size can be sensitive to the assumptions made in the calculations

- a small change in one of the assumptions can lead

- to substantial change in the calculated sample size.

- Often a simple formula can be used to calculate the required sample size.

- a small change in one of the assumptions can lead

- Firstly, investigators typically make assumptions

- it is necessary for researchers to balance

- the risk of incorrectly concluding that there is a difference (Type I error)

- when no actual difference between the treatments exists,

- with the risk of failing to identify a meaningful treatment difference when the treatments do differ(Type II error)

- Under the conventional approach, referred to as the statistical hypothesis testing framework

- the probabilities of these two errors are controlled by setting

- the significance level (type I error) and

- statistical power (1 minus type II error) at appropriate levels

- (typical values are two sided 5% significance and 80% or 90% power, respectively).

- Once these two inputs have been set, the sample size can be determined given

- the magnitude of the between group difference in the outcome it is desired to detect

- (the target difference).

- the magnitude of the between group difference in the outcome it is desired to detect

- The calculation (reflecting the intended analysis) is conventionally done

- on the basis of testing for a difference of any magnitude

- the probabilities of these two errors are controlled by setting

- the risk of incorrectly concluding that there is a difference (Type I error)

- A key question of interest is what magnitude of difference can be ruled out.

- The expected (predicted) width of the confidence interval can be determined

- for a given target difference and sample size calculation,

- The required sample size is very sensitive to the target difference.

- The expected (predicted) width of the confidence interval can be determined

- In more complex scenarios, simulations can be used

- It is prudent to undertake sensitivity calculations to assess

- the potential effect of misspecification of key assumptions such as

- the control response rate for a binary outcome or

- the anticipated variance of a continuous outcome

- the potential effect of misspecification of key assumptions such as

- It is prudent to undertake sensitivity calculations to assess

Specifying the target difference for a randomised controlled trial

- the specification of the target difference for a randomised controlled trial,

- a series of recommendations is provided in box 1 and table 1.

- Seven broad types of methods can be used

- to justify the choice of a particular value as the target difference, which are summarised in box 2

- Box 2: Methods that can help inform the choice of the target difference

- Methods that inform what is an important difference

- Anchor

- using either a patients’ or health professional’s judgment to define what an important difference is

- by comparing a patients’ health before and after treatment and then

- linking this change to participants who showed improvement or deterioration using a more familiar outcome

- Distribution

- determine a value based on distributional variation

- use a value that is larger than the inherent imprecision in the measurement and therefore

- likely to represent a minimal level needed for a noticeable difference

- Health economic

- use the principles of economic evaluation

- compare cost with

- health outcomes and

- define a threshold value for the cost of a unit of healt effect that a decision maker is willing to pay

- compare cost with

- to estimate the overall incremental net benefit of one treatment versus the comparator

- use the principles of economic evaluation

- Standardised effect size

- the magnitude of the effect on a standardised scale defines the value of the difference

- For continuous outcome, the standardised difference can be used

- e.g., Cohen’s d effect size

- the mean difference/the S.D

- e.g., Cohen’s d effect size

- For binary or survival(time-to-event) outcome, odds, risk or hazard ratio can be used

- no widely recognised cutoff points exist

- Anchor

- Methods that inform what is a realistic difference

- Pilot Study

- to guide expectations and determine an appropriate target difference for the trial

- Phase 2 study could be used to inform Phase 3 study

- Pilot Study

- Methods that inform what is an important or a realistic difference

- Opinion seeking

- the target difference can be based on opinions elicited from health professionals, patients, or others

- Possible approaches

- forming a panel of experts

- surveying the membership of a professional or patient body

- intervewing individuals

- Review of evidence base

- the target difference can be derived from current evidence on the research question

- Ideally, from a systematic review or meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

- In the absence of randomised evidence, evidence from observational studies could be used in a similar manner

- Opinion seeking

- Methods that inform what is an important difference

- Target difference should always be both important and realistic,

- which would seem particularly apt

- when designing a definitive (phase 3) superiority randomised controlled trial.

- In a sample size calculation for a randomised controlled trial,

- the target difference between the treatment groups strictly relates to

- a group level difference for the anticipated study population.

- the target difference between the treatment groups strictly relates to

- which would seem particularly apt

Reporting the sample size calculation

- The approach taken to determine the sample size and the assumptions made should be clearly specified.

- all the inputs and formula or simulation results,

- so that it is clear what the sample size was based on.

- critical for reporting transparency,

- allows the sample size calculation to be replicated, and

- clarifies the primary (statistical) aim of the study.

- all the inputs and formula or simulation results,

- approach with a standard trial design (1:1 allocation, two arm, parallel group, superiority design) and unadjusted statistical analysis,

- the core items are

- the primary outcome, the target difference appropriately specified according to

- the outcome type,

- the associated nuisance parameter

- (that is, a parameter that, together with the target difference, uniquely specifies the difference on the original outcome scale

- eg, the event rate in the control group for a binary primary outcome), and

- the statistical significance and power

- the primary outcome, the target difference appropriately specified according to

- the core items are

- More complicated designs can have additional inputs

- such as the intracluster correlation for a cluster randomised design

- When the sample size calculation deviates from the conventional approach,

- whether by research question or statistical framework,

- the core reporting set can be modified to provide

- sufficient detail to ensure that the sample size calculation is reproducible and

- the rationale for choosing the target difference is transparent.

- If the sample size is determined on the basis of a series of simulations,

- this method should be described in sufficient detail

- to provide an equivalent level of transparency and assessment

- this method should be described in sufficient detail

Discussion

- Researchers are faced with a number of difficult decisions when designing a randomised controlled trial, the most important decisions are

- The choice of trial design,

- primary outcome, and

- sample size

- The sample size is largely driven by

- the choice of the target difference

- The DELTA2 guidance provides help on

- specifying a target difference and

- undertaking and reporting the sample size calculation for a randomised controlled trial.

- The guidance was developed in response to a growing recognition from funders, researchers, and other key stakeholders (such as patients and the respective clinical communities) of a

- real need for practical and accessible advice to inform a difficult decision.

- The key message for researchers is the need

- to be more explicit about the rationale and

- justification of the target difference

- when undertaking and reporting a sample size calculation.

- Increasing focus is being placed on the target difference

- in the clinical interpretation of the trial result,

- whether statistically significant or not.

This post is licensed under CC BY 4.0 by the author.